How to Do a Patent Search Yourself

Conducting a patent search yourself can save thousands in legal fees and give you immediate insight into what’s already patented in your field. Many inventors skip this step, assuming it’s too technical or time-consuming, but the USPTO and other databases make it surprisingly accessible.

At Daniel Law Offices, P.A., we’ve seen firsthand how a thorough DIY search prevents costly mistakes down the road. This guide walks you through the tools, strategies, and pitfalls to watch for.

Which Free and Paid Tools Should You Use for Patent Searching

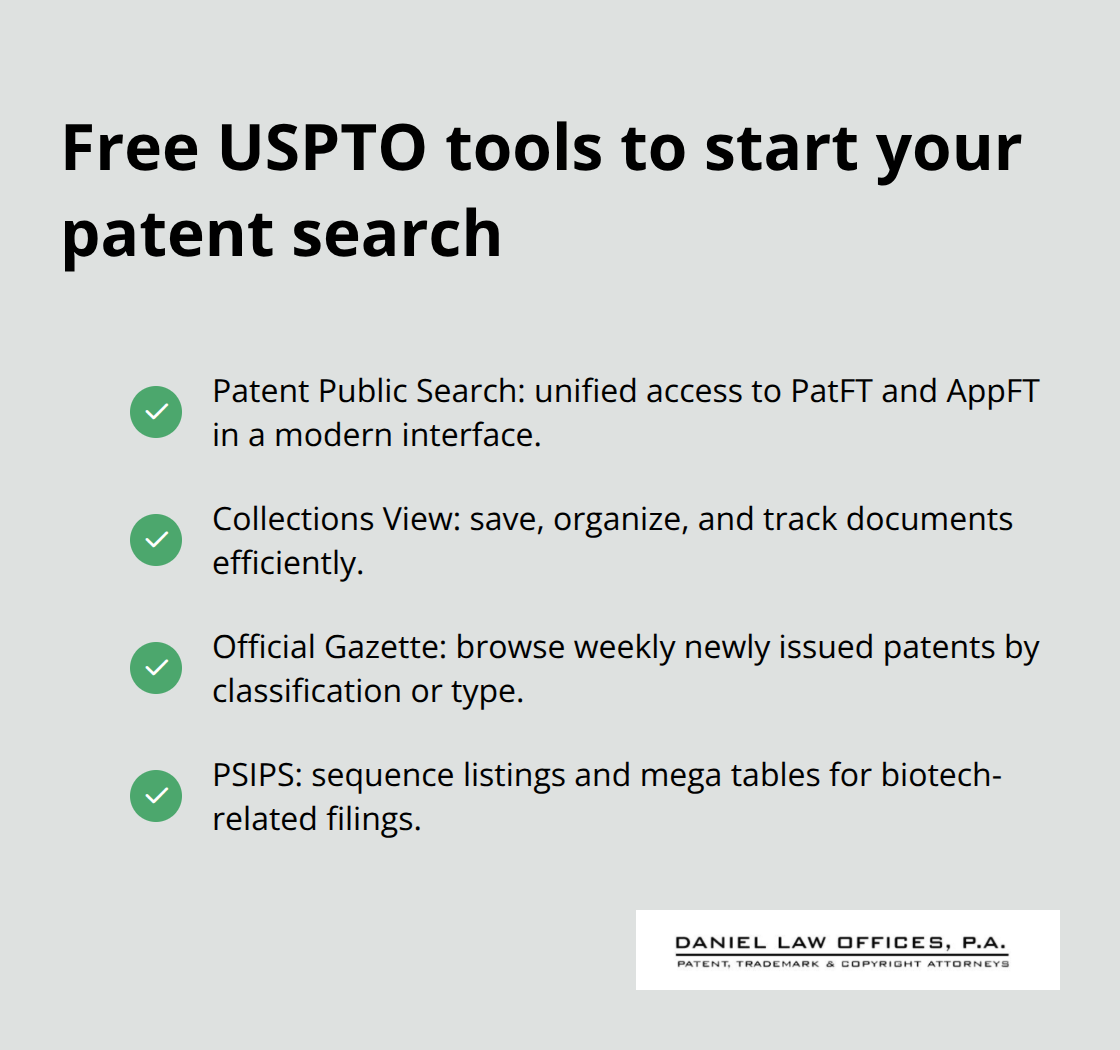

Start with Free USPTO Resources

The USPTO offers genuinely powerful free tools that rival what you’d pay hundreds of dollars for elsewhere. Patent Public Search is the modern interface you should start with-it replaced the older PubEast and PubWest systems and gives you access to both granted patents through PatFT and published applications through AppFT in a single search window. This matters because published applications often reveal competitors’ unreleased ideas before they become granted patents. The Collections View feature lets you save and organize documents as you work, which saves enormous time when you manage dozens of results. The Official Gazette, updated weekly by the USPTO, lets you browse newly issued patents filtered by classification or type, giving you a real sense of what’s trending in your technology area. If your invention involves biotechnology or sequences, PSIPS provides sequence listings and mega tables specific to US patents and applications. These tools cost nothing, yet most inventors either don’t know they exist or assume they’re outdated.

Paid Platforms Deliver Speed and Depth

Tools like PQAI, PatSnap, The Lens, and Orbit Intelligence exist because free databases have limitations. PQAI, which is open-source and aims for transparency, lets you describe your invention in plain English rather than forcing you to construct complex Boolean search strings-this matters because the same invention gets described a hundred different ways across patent documents. PQAI’s dataset covers roughly 11 million US patents and applications plus 11.5 million engineering and computer science research papers, so you catch non-patent literature competitors often miss. The tool shows you exact text snippets matching your query and lets you filter by publication date and document type. Paid platforms automate citation chasing across forward and backward references, which would take you hours manually. They also apply semantic AI to find conceptual overlaps you’d miss with keyword matching alone. If you search a crowded technology area, a paid platform’s speed and depth justify the cost. Niche fields often suffice with free tools alone.

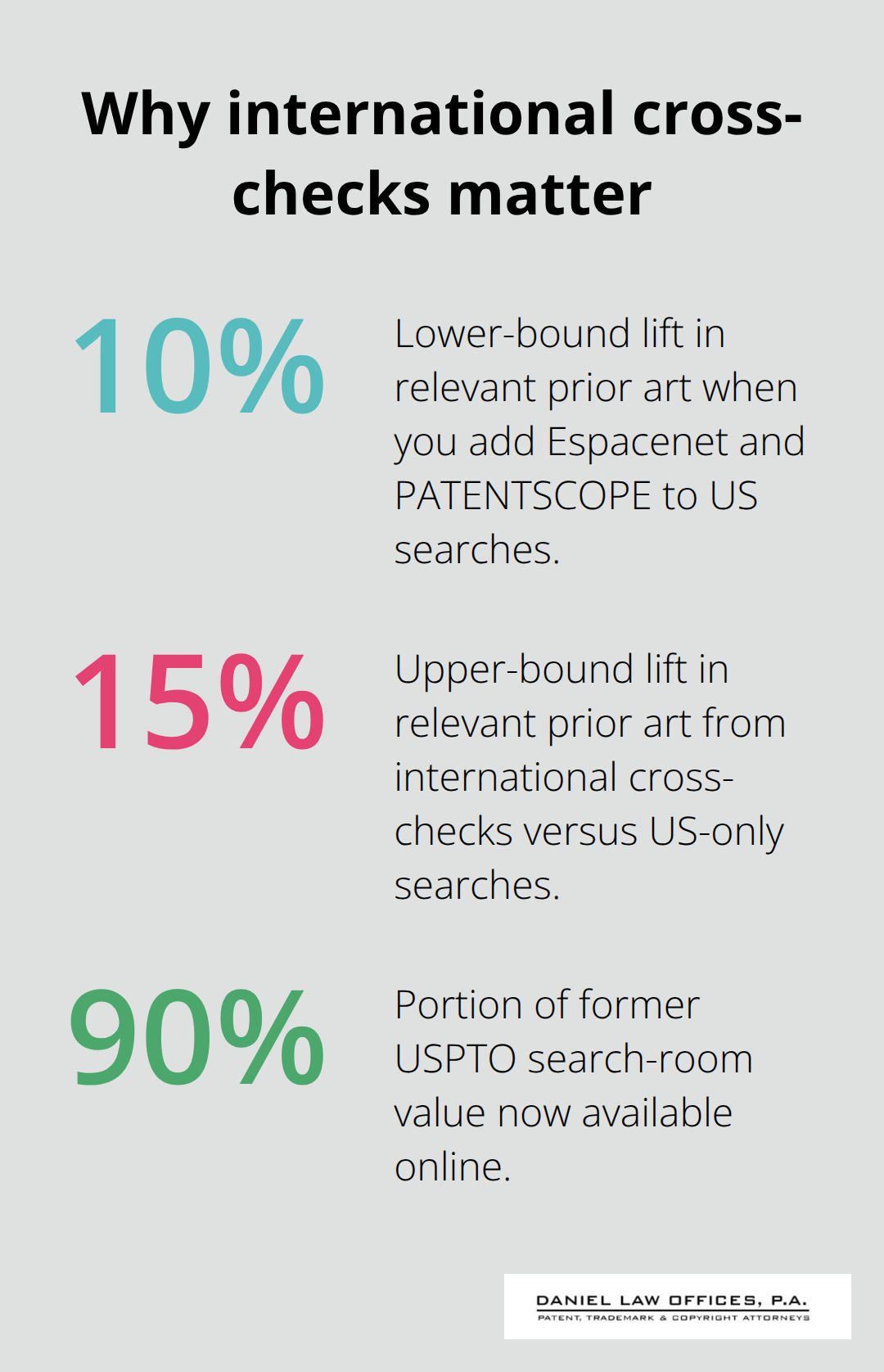

International Databases Reveal Hidden Prior Art

International databases are not optional-they’re essential. The European Patent Office’s Espacenet, WIPO’s PATENTSCOPE, Japan’s JPO, Korea’s KIPRIS, and China’s CNIPA all contain patents that won’t show up in US searches. Many of these platforms provide machine translations, so language barriers are minimal. The USPTO’s Global Dossier pulls file histories across the IP5 offices, and the Common Citation Document consolidates citations for patent families across jurisdictions-this gives you a unified view of prior art rather than hunting through five separate databases. A two-step approach works best: conduct your primary search through Patent Public Search or PQAI, then cross-check results against Espacenet and PATENTSCOPE to catch references not indexed in US databases. This catches roughly 10 to 15 percent more relevant prior art than US-only searches, according to patent professionals managing cross-border portfolios. Patent Assignment Search reveals ownership changes and licensing history, which matters if you assess freedom-to-operate or understand competitive positioning. The internet now provides roughly 90 percent of the value once provided by traveling to a physical USPTO search room, so geographic location no longer limits your access to comprehensive prior art.

With your tools selected and your search strategy mapped across free and paid platforms, you now need to identify the specific keywords and classification codes that will unlock the most relevant results.

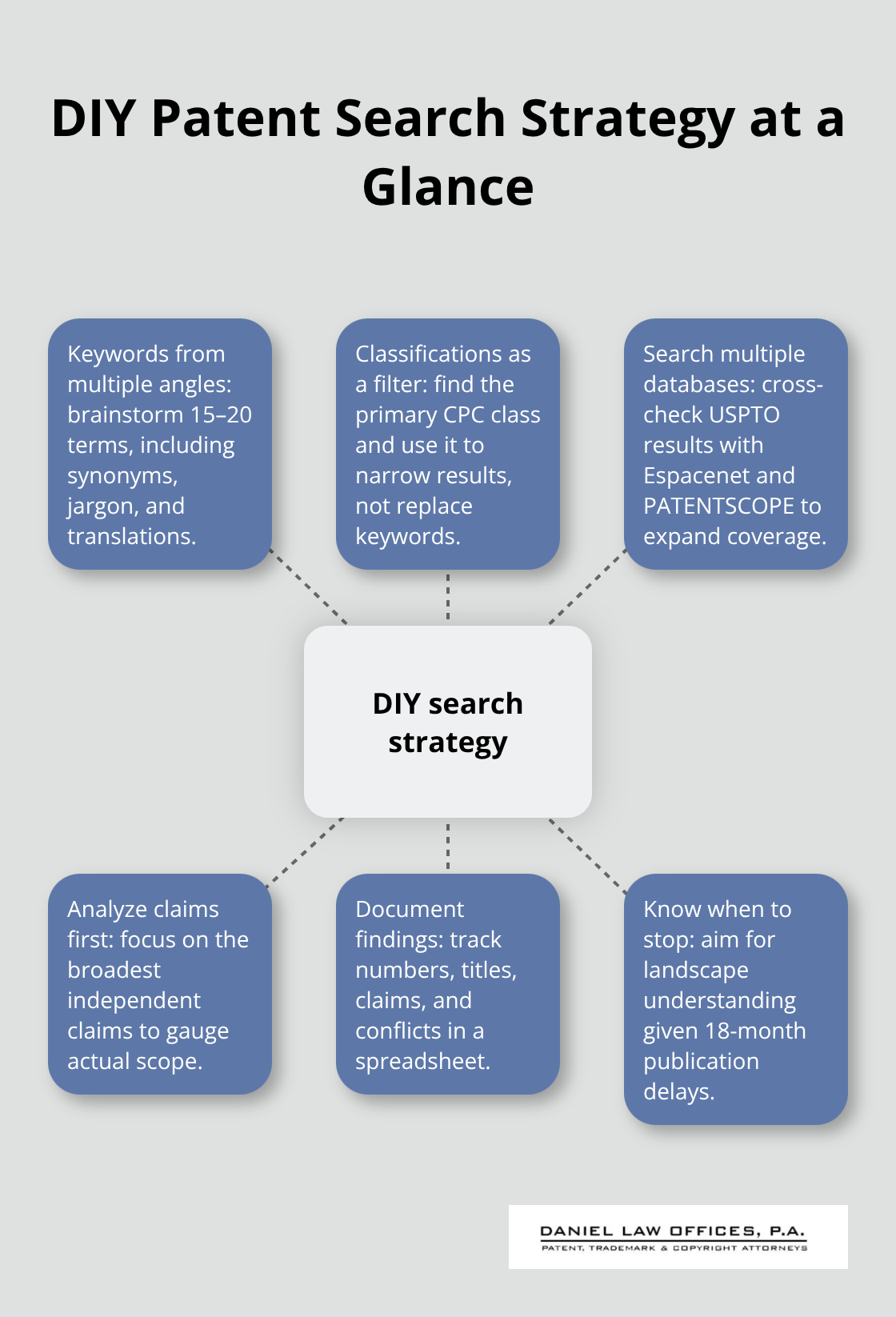

How to Build Your Search Strategy Step by Step

Brainstorm Keywords From Multiple Angles

Start with keywords that describe your invention from multiple angles. Most inventors brainstorm only the obvious terms, which guarantees you’ll miss relevant prior art. If you’re inventing a lightweight Bluetooth speaker with built-in flame, search for Bluetooth speaker, portable speaker, wireless audio device, camping light, flame effect, and LED lighting separately. Then combine these terms in different ways. Synonyms matter enormously because patent examiners and competitors describe the same concept differently. Industry jargon, foreign language translations, and even abbreviations reveal patents you’d otherwise skip. Once you’ve built a keyword list of 15 to 20 terms, move to classification codes.

Identify Your Classification Code

The Cooperative Patent Classification system organizes all patents into specific categories, and finding your invention’s primary CPC class narrows results dramatically. Patent Public Search lets you browse classifications by technology area, or you can search the MPEP to understand which class fits your invention. Don’t rely only on classifications though-many inventors make this mistake and assume that searching one CPC class covers everything. Use classifications as a filter to reduce noise, not as your primary search method. The USPTO’s How to Conduct a Preliminary U.S. Patent Search guide recommends a two-step strategy: first search keywords across both PatFT and AppFT in Patent Public Search, then refine by classification. This combination catches both granted patents and published applications that haven’t yet been examined.

Search Multiple Databases Simultaneously

Searching across multiple databases prevents the single biggest mistake DIY searchers make-assuming USPTO results represent the entire landscape. Start with Patent Public Search for US patents and applications, then immediately cross-check results against Espacenet for European patents and PATENTSCOPE for WIPO filings. This takes 30 minutes but reveals 10 to 15 percent more relevant prior art than US-only searches. After you’ve identified your most relevant patents, chase citations forward and backward. The References Cited section on every patent points to older prior art, while the Referenced By section shows newer patents that cite the original. Patent Public Search’s Collections View lets you save these documents and track them, or use PQAI to automate citation chasing across its 11 million US patents and 11.5 million research papers.

Analyze Claims and Document Your Findings

When you review results, focus on patents with claims closest to your invention’s core features. Read the claims section first, not the abstract-claims define what’s actually patented, and many inventions that sound identical in their abstracts have completely different claim scope. If a prior patent claims only a rigid frame while yours uses flexible materials, that distinction matters. Document everything you find in a spreadsheet with the patent number, title, relevant claims, and whether it conflicts with your idea. This record satisfies disclosure duties and helps you explain to a patent attorney why you believe your invention is novel. Stop searching when you’ve found enough prior art to understand the landscape, not when you’ve exhausted every possible result (the 18-month publication window means some competitor patents haven’t been published yet, and foreign-language materials or non-indexed documents will always exist beyond your reach).

Once you’ve completed your analysis and organized your findings, the next critical step involves understanding what your results actually mean and how to interpret the patents you’ve uncovered.

What Mistakes Kill DIY Patent Searches in Orlando, Florida

Limiting Your Search to the US Database Alone

Most inventors conducting their own patent searches make one fatal error: they treat the USPTO database as the complete universe of prior art. Patent Public Search is comprehensive for US patents and applications, but it represents only your domestic landscape. If a competitor filed in Europe, Japan, or China first, you won’t see it in Patent Public Search alone. The internet provides roughly 90 percent of the value once offered by physical USPTO search rooms, but that remaining 10 percent matters enormously when your patent’s validity depends on novelty.

Espacenet contains over 120 million patent documents from European and global sources, while PATENTSCOPE indexes WIPO filings that never appear in US databases. A two-database search takes 30 minutes but reveals 10 to 15 percent more relevant prior art than US-only searches according to patent professionals managing cross-border portfolios. You must search Espacenet and PATENTSCOPE alongside Patent Public Search, not as an afterthought. The Global Dossier and Common Citation Document consolidate results across the IP5 offices, so use these tools to verify whether competitors have protected their ideas internationally.

Confusing Patent Claims With Patent Abstracts

The second critical mistake involves confusing patent claims with patent abstracts. An abstract summarizes the invention in plain language, but claims define what’s legally protected. Two patents can describe similar-sounding inventions in their abstracts while having completely different claim scope. If you read only the abstract and conclude that prior art conflicts with your idea, you’ve reached the wrong conclusion.

Read the independent claims first, specifically the broadest claim in the patent. If the prior patent claims only a rigid aluminum frame while your invention uses flexible composite materials, that distinction matters. Document every relevant patent in a spreadsheet with the patent number, title, and specific claim language that either conflicts or differs from your invention. This record satisfies disclosure duties to the USPTO and helps a patent attorney assess your novelty position accurately.

Misinterpreting Whether Prior Art Actually Blocks Your Patent

Many inventors also misinterpret whether prior art actually blocks their patent. A patent that describes something similar does not automatically invalidate your application if your invention has meaningful differences in structure, function, or result. Consult the MPEP guidance on obviousness and non-obviousness to understand how examiners evaluate close prior art. Even if you find conflicting patents, strategic claim narrowing or design modifications can preserve patentability.

Incomplete applications that miss international filings or misread claim language lead to abandoned ideas that could have been protected. Stop reading when you understand the claim scope, not when you’ve memorized every technical detail. The distinction between what a patent claims and what it merely describes separates successful applications from rejected ones.

Final Thoughts

A DIY patent search reveals whether your invention has a realistic path to protection, but knowing when to hand off to a professional separates inventors who succeed from those who waste years on unpatentable ideas. If your search uncovers significant prior art that closely matches your core features, or if you struggle to interpret claim language and prior art relationships, that’s your signal to consult a patent attorney. The cost of professional guidance at this stage is minimal compared to filing an application that examiners will reject because you missed critical prior art or misread existing claims.

After you complete your search, organize your findings into a clear document showing which patents you reviewed, how they relate to your invention, and why you believe your idea remains novel. This record becomes invaluable when you file your application or discuss strategy with a patent attorney. If your search revealed no blocking prior art, move forward with confidence-if you found close competitors, decide whether design modifications strengthen your position or whether the landscape is too crowded for meaningful protection.

We at Daniel Law Offices, P.A. help inventors and businesses navigate what comes after the search. Our registered patent attorney guides you through drafting and filing applications with the USPTO, interpreting examiner rejections, and building a protection strategy that fits your business goals. Contact us to discuss your invention and learn how we can review your patent search findings and advise on patentability.